Understanding Train Etiquette in General

Japan’s train networks are a cornerstone of urban life, connecting millions of people daily in and around cities like Tokyo and Osaka. Their efficiency is supported by unspoken rules that help ensure a smooth and pleasant experience for most passengers. While these customs are not universal mandates and adherence varies among individuals, being mindful of them can contribute to a more harmonious journey.

Just the other day, I was getting off “my” commuter train, which, pre-Covid was running at 200% in the mornings, I saw a tourist-family of five queuing for the door I was getting off. Parents and teenage children all looked clearly overwhelmed. It looked like they had already skipped a couple of trains, hoping the next would be less crowded. The crowded conditions may indeed be challenging for those unaccustomed to standing in close proximity to strangers for long (or even short) periods.

During quieter periods, when trains are less crowded, many passengers tend to avoid loud conversations, phone calls, or disruptive behaviour, respecting the shared space. It is common for people to manage their belongings by holding backpacks in front of them or storing larger luggage on overhead racks to maximize space. Boarding and exiting trains is usually orderly: passengers line up, wait for others to alight, and then board. These practices, while not followed by everyone, reflect an underlying commitment to minimizing stress during daily commutes.

As a visitor, observing these unspoken rules can make your experience smoother. Simple actions like keeping your phone on silent mode or refraining from eating on the train can show consideration for fellow passengers and contribute positively to the atmosphere.

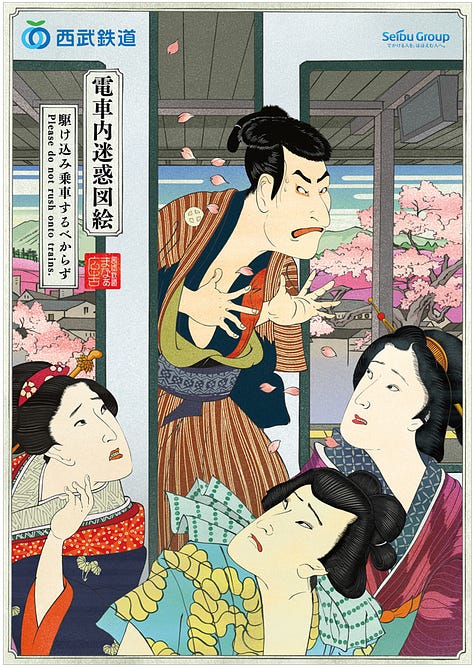

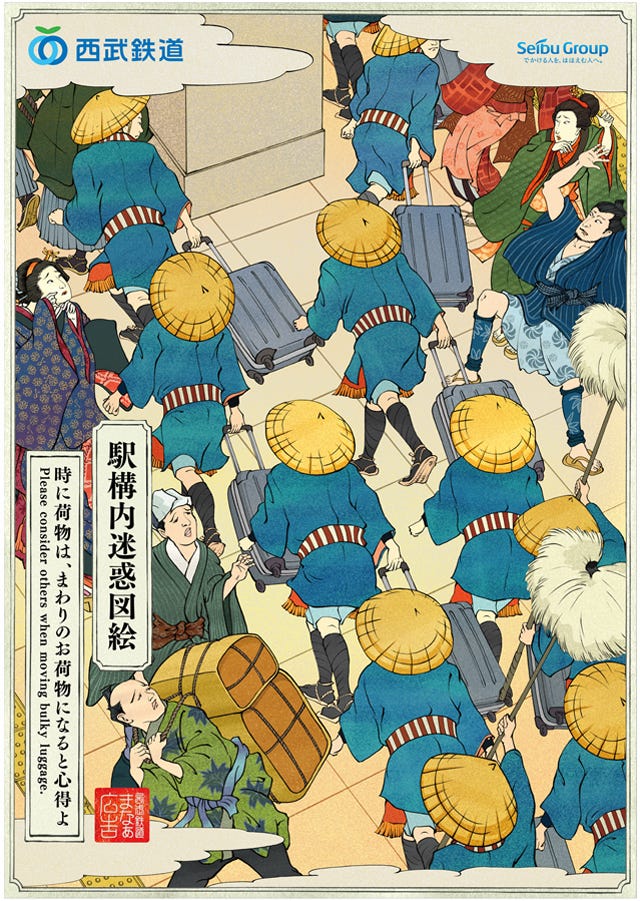

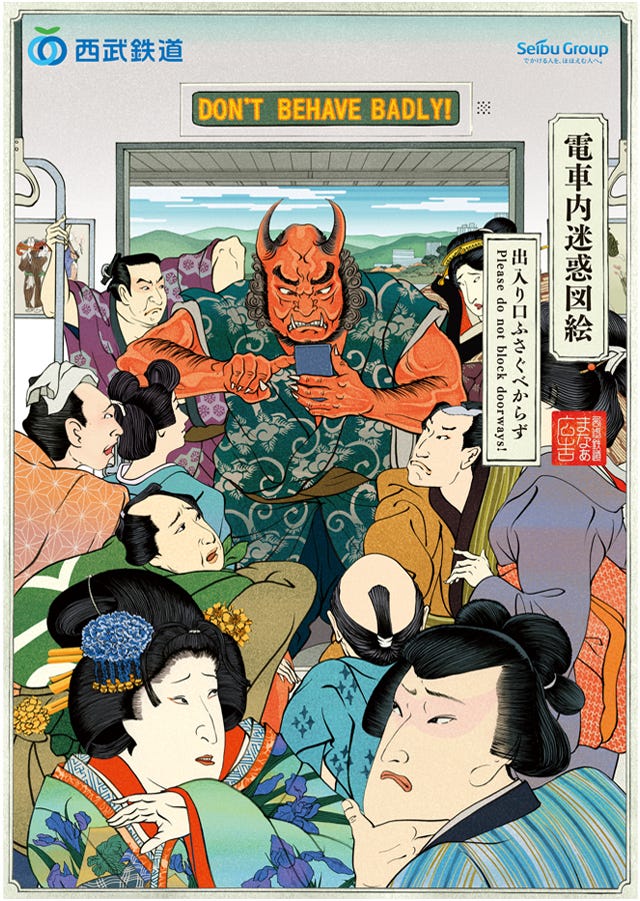

For reference, here are a couple of etiquette posters from the Seibu Line, that runs from Shinjuku and Ikebukuro to Western Tokyo.

Credit: Seibu Group

Why Tourists Should Consider Avoiding Rush Hour

During rush hour, Tokyo’s trains often operate at over-capacity. At 100%, passengers can comfortably hold onto a strap or pole. At 200%, bodies press against each other, though one might still manage to read a magazine (in one hand). At 250%, movement becomes impossible, with passengers packed so tightly that even raising a hand is difficult.

Credit: Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Railway Bureau . (2008). “Sūji de miru tetsudō 2008” .

I still vividly remember my first really packed metro ride, heading to an embassy appointment at 8 am during peak rush hour on one of the worst lines (see below). The intensity of the crowd was unlike anything I had experienced before. Naively, I planted myself near the door, thinking it was the best spot for a quick exit. It was a 40-minute ride, so I could have easily taken a seat further inside if I had thought it through. But I was afraid I would not be able to leave. As more people pushed in, I clung to my spot, trying hard to resist the flow. At one point, I felt the presssure of bodies all around me and blurted out, “Itai!” (痛い – “Hey, that hurts!”). It was a moment of frustration and discomfort, but also one of complete misunderstanding of the choreography on trains.

Looking back, I realize how my inexperience made the journey more difficult not only for me but likely for others around me. In my effort to hold my ground, I disrupted the flow that regular commuters navigate with practised precision. I understand now that moving into the car, even if it feels counter-intuitive at first, is part of an unspoken agreement that ensures everyone can board.

If I met my younger self on that train - I’d give myself a firm talking-to - not just for the naïveté of the situation, but for the missed opportunity to adapt and learn from the experience in the moment. That first “real” rush hour taught me not only how to navigate a crowded train but also how to read the subtle social cues that govern shared spaces in urban spaces. It now understand the importance of adapting to shared spaces, a valuable takeaway for any public setting really.

Such experiences can be disorienting for newcomers but offer valuable lessons in the mutual awareness and small courtesies that make train travel more manageable While crowded trains may overwhelm some, others adapt more easily. Travelling off-peak allows visitors to appreciate the system’s efficiency without stress, and larger groups might consider alternatives like taxis for convenience.

Tips for Travelling During Rush Hour

If you do find yourself needing to travel during rush hour, these suggestions can help make the experience more manageable:

Positioning: Move toward the centre of the carriage if travelling longer distances. For shorter trips, it’s okay to stay near the doors, but avoid blocking others. If needed, step off the train temporarily to let people alight.

Balance: Keep your feet slightly apart to steady yourself as the train accelerates and brakes.

Bags and Luggage: Avoid travelling with lots of luggage. If you have a backpack, hold it in front of you to minimize inconvenience to others. While some argue the back is better, front-carrying is a more common sight during commutes. Avoid placing bags on the floor, as retrieving them in a crowded train can be difficult. Big suitcases are in the way - try a taxi if you are to going to the airport - or a delivery service, when you move to another hotel in another city.

Exiting the Train: Move toward the doors only when the train has stopped. Don’t hesitate to ask others to let you through by saying “Orimasu” (in IPA: /oɾi.masu/ ; “I’m/We’re getting off”) or simply “Sorry” in English. If you’re in a group, you will get torn away from each other. Tell all members when to get off, and do not try to stick together, it’s close to impossible.

Situational awareness is also key. Avoid using your phone for calls, cover your mouth and wear a mask during flu season, and be mindful of others’ comfort by avoiding strong fragrances. In shared spaces like offices or trains, many people appreciate minimal use of fragrances

Embracing the Experience

The worst lines during rush hour (2023 data) are Nippori Toneri Liner (171% capacity; towards Nishi-Nippori), Hibiya-Line (162% between Minowa and Iriya), Saikyō Line (160% between Itabashi and Ikebukuro), Chuō Line (158% between Nakano and Shinjuku).

Many find ways to make their commute productive or pleasant. Some use their train time to catch up on reading or podcasts. Others prefer early morning trains, even if it means starting their day at dawn, trading peak crowds for a more comfortable ride. The increasing flexibility of work hours and remote work options has also helped some commuters avoid the busiest times altogether.

For visitors, the most practical approach is to plan activities that don't require rush hour travel. If peak-time travel is unavoidable, come prepared: travel light, know your route, and accept that it will be crowded. The experience might be challenging, but it's temporary - and there's always the option of a coffee shop breakfast until the rush subsides.

I enjoyed reading this, thank you.

Thanks so much. I think tourist on trains is one of the Tokyoites biggest pet peeves and I see so many scared tourists during my morning commute so it felt a good topic to write about.

https://www.nishitetsu.co.jp/ja/news/news20241219/main/0/link/24_104.pdf